Court Robes (The Official Robes of Imperial Era China)

The Imperial Robe, also called the Court Robe, was the court dress – and exclusive reserve – of ancient Chinese emperors. They date as far back as the Zhou (BCE 1027-221) Dynasty. They were always of a strong yellow color, a color that had come to be associated with the emperor and which tradition continued all the way through the Qing (CE 1644-1911) Dynasty. Not a lot is known about the other particulars of the early royal robes, except that the images they bore were copied from murals and paintings of their period, including lacquer paintings, that generally echoed the theme of the supreme, unifying power of the emperor.

We also know that these early emperors wore a special headdress, or stylized crown, together with the Court Robe on official occasions, a headdress that is reminiscent of the odd cap worn by graduating high school students in the U.S., namely, a flat square with tassels in front and in back that was attached, with the help of special pins, to the hair, which was done up in a bun, or knot, on the top of the head (from whence the American high school graduating cap – they also wear a gown that might be likened to a simplified, or stylized, Court Robe – is derived is anyone’s guess, but it may very well have its origins in Chinese culture).

To stabilize the crown in windy conditions, silk ribbons could be attached to the pins that secured the crown to the head on either side, and these ribbons were then tied under the chin. A small jade pendant hung from the underside of the crown, alongside the emperor’s right ear, symbolizing the need to always be vigilant of whispered plots against the emperor’s throne, and, by extension, against his people.

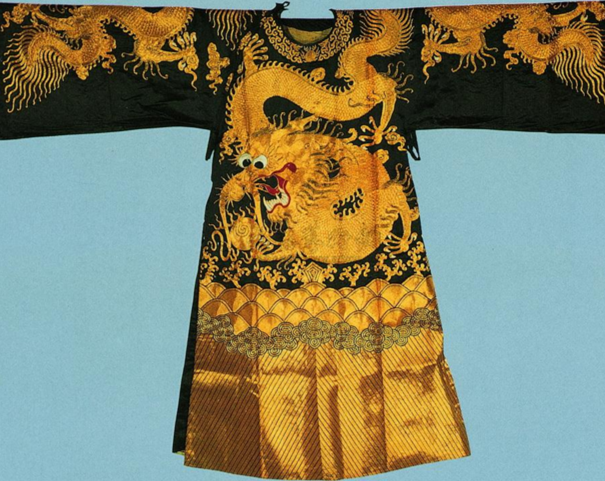

In time, Court Robes began to be adorned with images of dragons, and yellow robes came to be worn by all of the males of the emperor’s immediate family, albeit, the bright yellow (alternatively, deep or pure yellow) color was reserved for the emperor, while paler shades of yellow were worn by the emperor’s sons – i.e., the heir apparent and his brothers.

In time, robes in other colors were worn by other royal princes beyond the immediate royal family, such as the emperor’s brothers and their sons, these robes being of darker colors such as brown, blue and blue-black. At some point in the development of these traditions, certain fixed “rules” emerged, besides the convention of reserving the purest yellow color for the emperor’s Court Robe. These included embroidering a specific number of dragon images on the robe, depending on whether it was the emperor’s robe (9 dragon images) or a prince’s robe (any number less than 9), and the number of claws on the dragon’s feet also reflected this same hierarchy – 5 claws for the feet of dragon images on the emperor’s robe, 4 claws for the feet of dragon images on a prince’s robe.

The number 9 was considered uniquely auspicious, it being the largest single-digit odd number, and therefore it was reserved for the emperor. The number 5 was also considered an auspicous number for the emperor, since it lies precisely in the middle – thus signifying harmony – of the single-digit odd numbers (1-3-5-7-9). Therefore the 9 dragon images that were embroidered on the emperor’s Court Robe, now called a long pao (“Imperial dragon robe”), were placed in such a way that precisely 5 of the dragon images were visible both in front as well as in back of the long pao. The robe worn by princes was called a mang pao (“royal dragon robe”).

The pattern for the dragon images on the long pao was as follows: two dragon images were embroidered on the lower part of the robe (roughly at the upper thigh level) – front and back – on either side of center, where the robe proper borders the split section below, which section was split down the center in front and in back, and on either side, for ease of sitting. One dragon image was embroidered on the center of the robe’s chest area – and correspondingly on the back area – while a dragon image was embroidered on each shoulder.

From the front, and viewing the robe from top down, one saw the two dragon images on the shoulders plus the two dragon images near the thigh areas plus the dragon image in the center of the torso (the chest, in this case). The same view applied as well from behind, except that the torso dragon image was embroidered between the shoulder blades. Note that the mang pao at this time only had two slits, one on either side, so as to further distinguish its inferior rank from that of the long pao (an emperor apparently deserved to sit more comfortably).

As time passed, this fixed system got more and more “corrupted”, with the long pao becoming the royal robe worn by all male members of the immediate imperial family, and with the mang pao being worn by lesser princes as well as high-ranking male public officials. These robes were still Court Robes.

Dragon Robes

Eventually, a variant type of dress robe was developed for outdoor activities, especially for horseback riding. This robe, called simply a Dragon Robe (ji fu, or “festive dress”), came to overshadow the Court Robe during the Ming (CE 1368-1644) Dynasty, as it was longer, more voluminous (the slit section at the bottom of the robe was longer, extending almost to the ground and covering the thigh while on horseback almost like a knee-length version of the cowboy’s leather chaps), and cut in a more masculine style, all of which made it popular among China’s emperors, who were becoming ever more present in the daily lives of their citizens.

The Ming Dynasty Dragon Robe, though initially rejected by the Manchu emperors of the Qing Dynasty (Ming Dynasty emperors were of Han origin), was eventually embraced with a vengence, as it were, by Qing Dynasty emperors, during which period the Dragon Robe reached its pinnacle as an article of fashion clothing among China’s emperors. By this time, there were also Dragon Robes for all high-ranking public officials, as well as Dragon Robes even for some lesser-ranking public officials.

The emperor’s Dragon Robe of the Qing Dynasty period was a thing of beauty which, at the same time, symbolized the power and grandeur of the emperor. Its intricately embroidered motifs often suggested the cosmos interlaced with earthly elements such as stylized clouds, waves, mountains and li shui, or a series of 5 different-colored diagonal stripes symbolizing deep standing water. Some royal Dragon Robes depicted more familiar earthly images, including towering pagodas, on the lower, split section of the robe, with skies – or heavens – embroidered on the area above, in which dragons flew among what would seem to be heavenly bodies.

The opulence of Qing Dynasty emperors, at least up until the middle of the Qing Dynasty, was fully mirrored in their Dragon Robes, the finest of which were made of the finest silk. The dazzling styles and patterns that characterized the emperor’s Dragon Robes were the exclusive reserve of the emperor. They were adorned here and there with gold thread, and the motifs were embroidered using a type of complex and time-consuming weaving technique called kesi, which is similar to the weaving technique that goes into the making of tapestry. Qing Dynasty Dragon Robes came in a multitude of styles to fit all occasions, from riding and hunting to more stately, ceremonious occasions, while the accoutrements that adorned them – from crowns to belts to sashes – were embellished with magnificently crafted, inlaid jewels such as emerald and jade.

Leave a Reply